In my customized Google news, I have a category for cosmetic surgery. Most items that turn up are self-serving PR announcements, but recently there was lengthy coverage of the death during cosmetic surgery of aspiring Chinese pop star Wang Bei.

In my customized Google news, I have a category for cosmetic surgery. Most items that turn up are self-serving PR announcements, but recently there was lengthy coverage of the death during cosmetic surgery of aspiring Chinese pop star Wang Bei.

The details are tragic: She was only 24. Ironic: She was already beautiful. And dramatic: Her mother was having the same procedure at the exact same time. So her mother woke up to discover her daughter was dead. Or perhaps not. According to conflicting reports, her mother was told nothing until the next day. The news reports out of China do not strike me as especially reliable.

For example, Wang Bei’s death was first reported as an anaesthetic accident, but the majority of stories describe the cause of death as bleeding from the jaw. Wang was having facial bone-grinding surgery “to make her jaw line fashionably narrow and her face smaller.” (Chinese women are said to prefer an oval face shaped like a ”goose egg.”)

The blood from Wang’s jaw drained into her windpipe, and she suffocated. Is that an “anaesthetic accident?” Wang’s surgeon claims the operation was a success and that Wang died of an unexpected heart problem several hours after the procedure.

The Chinese Ministry of Health asked the provincial health department (where the surgery took place) to conduct an investigation and report back as soon as possible. Wang died on November 15, and there is still no official word.

The sociologist and the plastic surgeon

Press coverage of the Wang Bei story – in addition to describing the young woman’s failed attempt to become a successful entertainer after her 2005 appearance on the Chinese equivalent of American Idol — was almost entirely about the importance of finding a qualified surgeon for your next cosmetic procedure. This is big business in China. In 2009, the Chinese spent $2.2 billion dollars on three million procedures, a figure that grows annually by 20%. China ranks third highest in the world in number of procedures (after the US and Brazil), and it’s number one in Asia.

There were a few – but not many – comments on why an attractive 24-year-old would want her jaw shaved. Typical was the following, which juxtaposed the question of motivation with the affirmation that, of course, a young girl wants cosmetic surgery.

Xia Xueluan, a sociologist at Peking University, told the Global Times that he also strongly disagreed with undertaking cosmetic surgery simply in order to improve one’s looks.

“The concept of beauty has also been greatly distorted nowadays,” he said. “Doing plastic surgery reflects people’s vanity and lack of confidence about themselves.”

A plastic surgery expert surnamed Jia at the PLA 309 Hospital in Beijing told the Global Times that it’s understandable that young women wish to have surgery to improve their looks – but he added that they should choose credible and qualified hospitals and doctors to avoid fatal accidents.

The sociologist versus the medical profession. I wonder whose voice the public prefers?

Fixing what can be fixed: The moral choice

In his wonderful essay “Emily’s Scars,” sociologist Arthur W. Frank raises the question: Where do we draw the line when it comes to “fixing” the self?

Is there some core of me that I should work with, not work on, or are some body parts no more than unwanted contingencies, like warts, that temporarily intrude on my life? If the latter, is the decision to fix determined only by a comparatively simple cost- and risk-benefit assessment? Need I ask only whether the promised improvement will be worth the time, trouble, and pain to me that the fixing involves?

Frank goes on to distinguish protectionist from Socratic bioethics. Protectionist bioethics was the prevailing response to Wang Bei’s death. The consumer of cosmetic surgery should be protected from harm. Doctors should be adequately trained and highly competent. There should be full disclosure of any risks. It all boils down to a cost-benefit analysis of a consumer purchase: What exactly am I getting, what is the benefit, what is the cost, and what is my risk.

Socratic bioethics, on the other hand, digs a little deeper. It asks – Socratically enough – what is the good life and what should health mean in this good life. When we choose to have cosmetic surgery – on our faces, our feet, our thighs – we tell ourselves this is entirely a personal and private decision that affects only the individual patient/consumer. But in fact, each one of us who makes the decision to have cosmetic surgery changes the standards of acceptable appearance in which everyone else must live. In that sense, the decision to have cosmetic surgery is communal and thus ultimately moral.

Fifteen minutes of fame

Who set the standards of appearance that prompted Wang Bei to undergo surgery? Should we condemn individuals, the media, celebrity culture, consumer culture, the competitive nature of modern life?

Who set the standards of appearance that prompted Wang Bei to undergo surgery? Should we condemn individuals, the media, celebrity culture, consumer culture, the competitive nature of modern life?

After her unsuccessful appearance on SuperGirl — a hugely popular singing contest in which the television audience votes on the winner (democracy in action in China) — Wang Bei took part in Dream China, a 2006 talent competition. Using her modest fame from SuperGirl, she secured a number of media appearances in the following years. She had hoped to sign with a record label, but this never happened. Her performances in subsequent competitions are described as “lackluster.” By the summer of 2010, she was singing in a bar in the industrial port city of Qingdao.

My favorite bioethicist, Carl Elliott, believes the issue of appearance boils down to the logic of consumer culture.

You can still refuse to use enhancement technologies, of course – you might be the last woman in America who does not dye her gray hair, the last man who refuses to work out at the gym – but even that publicly announces something to other Americans about who you are and what you value. This is all part of the logic of consumer culture. You cannot simply opt out of the system and expect nobody to notice how much you weigh.

Nor, evidently, can you compete for fame without acquiescing to the rising standards of appearance set by those who opt for cosmetic surgery. Standards, as Jonathan Metzl puts it in another context, that are “wholly mainstream and impossible to attain.”

Wang Bei had achieved sufficient fame to have fans. One report noted that some of those fans – on hearing the news of her death – accused her of staging a publicity stunt to attract attention. Alas, the news was true. In her death Wang Bei found the fame that had eluded her in life.

Update 12/6/10:

Wang Bei’s Ultimate Sacrifice to Beauty

This is not an official report on Wang’s death, but observations from an anonymous doctor who was part of Wang’s “rescue” team. Other sources have also reported on Wang’s previous cosmetic surgeries.

An error on the part of the surgeon … led to a bleed from Wang’s lower jaw into her trachea. … As she was under general anesthetic, by the time surgeon realized what had happened she had already gone into shock. …

“She had already undergone facial surgeries on her eyes, nose and lower jaw in addition to the bone-grinding procedure mentioned on the Internet. Respiratory tract obstructions are a risk during simultaneous surgery on the nasal cavity and lower jaw, which is why such cases need careful observation,” the doctor said, adding, “Wang didn’t die during surgery but in the observation period afterwards. The surgery called for tight bandaging over the patient’s chin and mouth. As the nasal surgery impeded nasal breathing, assisted respiration was necessary. It appears that Zhong’ao Cosmetic Surgery Hospital was deficient in its observation procedure after surgery, and is hence responsible for Wang’s death.”

Update 12/7/10:

Plastic Surgery & Chinese Singer

Here’s speculation from the California Surgical Institute Blog on what may have happened (purely hypothetical), plus reassurance that it wouldn’t happen here.

[T[he most likely scenario was that the surgeon nicked a vein, allowing blood and mucous to trickle into Wang’s intubation tube and into her lungs. In short, she drowned on the table. Or, her lungs were so stressed by the fluids, they sprung a heart attack.

Can that happen in U.S. plastic surgery? Given a board certified plastic surgeon working with a board-certified anesthesiologist (who is another medical doctor) it is very, very unlikely.

Update 12/22/10:

As China’s obsession with plastic surgery grows, so too do the pitfalls (Washington Post)

A comment from the Western press on the popularity of cosmetic surgery in China. Number of surgeries much higher than officially reported.

“I feel people have a higher standard of beauty right now,” [Dr.] Xu [Shirong] said. “I tell many of my patients they score 98 already, and that’s good enough, with no need to pursue a perfect 100. But most of my patients still choose to add those two missing points.”

Update 4/23/11:

For Many Chinese, New Wealth and a Fresh Face

A New York Times story on the popularity of cosmetic surgery in China answers the question: Why have we not heard the results of a promised investigation into the death of Wang Bei?

Mr. Ma likened the industry to a medical “disaster zone,” with frequent accidents. His point was underscored when a 24-year-old former contestant on the Chinese reality show “Super Girl” died after her windpipe filled with blood during an operation to reshape her jaw in Hubei Province.

Health officials demanded an inquiry. But Mr. Zhao, who also serves as the vice director of Beijing’s government-run Plastic and Cosmetic Surgery Hospital, said it was impossible to gather evidence because the body was quickly cremated — a common practice in China when hospitals privately settle malpractice claims.

Related posts:

Character, personality, and cosmetic surgery

Bibi Aisha: Fixing what can be fixed

Mutilated Afghan woman on the cover of Time

Afghan women empowered to practice beauty

The tyranny of health then and now

The tyranny of health

Actions surrounding the moment of death are highly symbolic

Resources:

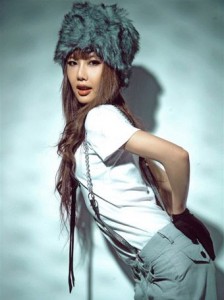

Image source (head shot): N24

Image source (pose): Asianbite

China’s ugly obsession, Sydney Morning Herald, December 2, 2010

Zhang Xiang (ed), Beauty has an ugly side, Xinhua News Agency, November 30, 2010

Jin Jianya, Beijing woman dies during plastic surgery procedure, Global Times, November 26, 2010

Arthur W. Frank, Emily’s Scars: Surgical Shapings, Technoluxe, and Bioethics, Hastings Center Report, March-April, 2004

Jonathan Metzl and Anna Kirkland, editors, Against Health: How Health Became the New Morality

I have been thinking about this since I first read it last night.

Generally I think when we generaize from the specific to everyone we tend to paint ourselves into a corner.

Despite the media, celebrity culture, consumer culture, and competitive culture everyone is ultimately at rock bottom, responsible for their own decisions. No one forced Wang Bei to undergo cosmetic surgery. She is the one who made her own decision. She is the one who wanted to be a part of the media, celebrity culture, consumer culture, and competitive of the entertainment world.

No one can prevent or stop the need some people have for being a star and always in the limelight. That goes to the complex world of personality and the many factors that shape it.

Beyond making sure that plastic surgeons are licensed and have clean safe sites to perform such surgery I don’t think there is anything society can, or should do.

I nor society at large cannot stop dumb people, or low-self-esteem people, or star mentality folks from making decisions that negatively affect them. No government program can stop people obsessed with stardom.

Humans have always exercised free will and self determination one way or the other.

I think some people, “can [you] compete for fame without acquiescing to the rising standards of appearance set by those who opt for cosmetic surgery.” We just don’t hear about them.

Yes, yes and yes. But … Wang Bei is merely symbolic of the millions of people (mostly women) who are subtly and not so subtly pressured (consciously and unconsciously) to conform to a certain standard of appearance. There is a bias towards beauty which we just accept. It’s all good and well to say this particular individual was exercising her free will and has only herself to blame, but discrimination of any sort will eat away at someone, even if they’re smart and have a healthy quota of self-esteem.

Yesterday I had to fill out a form at a bank that was written in financial legalese. When I didn’t understand something, the young woman I was dealing with was sarcastically snide about what she thought was perfectly obvious. I noticed that this made me felt lousy. (Very briefly — I know this was her problem, not mine.) And maybe it’s just that the subject’s been on my mind lately, but it occurred to me that this felt like appearance discrimination. (I was wearing a sweat shirt.) I wondered: If I were a few decades younger and/or fashionably dressed, would I have been treated differently?

I don’t want to live in a society where I need Botox and Manolo Blahnik’s to be treated with respect. I suppose I should be grateful that it hasn’t happened to me more often. I have the advantage of being white and not overweight. But when I think about what other people (women especially) experience, it makes me angry.

As Deborah Rhode writes in The Beauty Bias: “The preoccupation with female appearance encourages evaluation of women in terms of sexual attractiveness rather than character, competence, hard work, or achievement. Although some women benefit from their beauty, it is not a stable form of self-esteem.”

Also: “Customers of a ‘family restaurant’ who want what a Hooters’ spokeswoman described as a ‘little good clean wholesome female sexuality’ are no more worthy of deference than the Southern whites in the 1960s who didn’t want to buy from blacks or the male airline passengers in the 1970s who liked stewardesses in hot pants.”

Yesterday I came across a comment on the book Why We Disagree About Climate Change: “People map onto climate change their own vision of what kind of world they’d like to live in and these views embody our values, our culture, and — just like on any big issue — we have fundamental disagreements across society about the answers to those questions.”

I think cosmetic surgery is an opportunity for a public discussion of what type of society we want to live in. What do we value, and what are the consequences of choosing to value consumption, celebrities, and competition? And is it really a choice? The beauty business is a multibillion dollar industry that has a vested interest in perpetuating increasingly higher standards of appearance.

I don’t see it as all that different from questions about the food industry, which argues that people want to eat high fat, sweet, salty food. People should be free to choose what they prefer. The tobacco industry believes people should be free to indulge in the pleasure of smoking. At what point do we say, Hey, look, we’re killing ourselves here. And who should say that?

I find this a very difficult question to answer: If our health and the quality of our lives are determined by the financial interests of a wealthy minority, where do we draw the line between freedom of choice and the nanny state? I don’t advocate government regulation. I have a modest libertarian streak. I do feel there should be greater public awareness/discussion/education that allows people to recognize the forces and influences at work. Then they should be free to choose. That’s why I want to write more about this topic.

No one should tell me not to eat chocolate cake. And no one should tell me not to get a nose job. But as I wrote in a previous post (http://bit.ly/gUYl4O) about how my mother suffered from her vanity (and where I used the same Carl Elliott quotation), I wish for her sake – and for all women — that we lived in a society less obsessed with appearance.

No one can make you (pressure you) to do something you really do not want to do. As a college psych professor I had always said, “People do what they want to do and make up their excuses afterwards.”

In his ground breaking book, Psycho-Cybernetics, Dr. Maxwell Maltz, a plastic surgeon too, discovered that, “his plastic surgery patients often had expectations that were not satisfied by the surgery.” (from Wikipedia.)

In other words, there is a personality or psychological need within some people that seeks them to have plastic surgery to fill a hole inside them. I think people who seek fame and want to go into the entertainmet industry, like Wang Bei, by and large have a certain personality type. And it is largely based on a need for constantly being in the spotlight, and a need for constant applause or approval. The roots of these needs would be many and complex, but could include genetics and parenting style.

No amount of discussion or education will overcome that. It would take yeras of psycho-therapy, and that may not be successful either.

All of us are bombared with images of Hollywood’s, the media’s, and the fashion industry’s idea of what is “ideal” beauty. But not all of us choose to have plastic surgery.

Number one, it is expensive. Most of us can’t aford it.

I also wondered just how big or what the scope of plastic surgery is. So I did a bit of research. The most recent data I could find was for 2001-2008. This is statistical data for the U.S. only.

In 2008, while the percentage of procedures went up over the previous year, 10.2 million procedures were done in 2008, the majority being Botox injections. The population of the US for the same year was (estimate) 312 million. 10.2 million when compared to the entire population is relatively low. And the majority of people having such elective surgery are generally older, in their 40’s or 50’s, not young women.

Compared to say the number of American adults who cannot read (32 million in 2003 or 14%) the scope of the issue is not all that high. And not being able to read is something that can be more easily changed as it is simply teaching a skill. Ending elective plastic surgery is not skill based but, psychologically based.

I personally belive that rank sexism and misogyny in Amerioca is a MUCH bigger problem than plastic surgery.

You write: “I do feel there should be greater public awareness/discussion/education that allows people to recognize the forces and influences at work. Then they should be free to choose. That’s why I want to write more about this topic.”

I applaud your efforts. I agree that knowledge is always good. But knowledge has its limitations. And as a teacher by training and education, it hurts me to acknowledge that. Most people are not swayed by logic or facts. Most people are swayed by emotion.

Finally, if I had encountered someone who treated me like you were treated at a bank recently, I would have thought it was another example of today’s young people having poor customer service skills and being a product of the self-esteem culture too prevalent in today’s homes and schools.